Shortly after I got to Charleston, I suspect sometime during my first year, we had an event on campus that I sent out broad community emails to advertise. CofC is a campus that has very, very few spaces that are accessible. I got an email from a community member I didn’t know who told me in pretty clear-cut terms that I’d scheduled an event in an unaccessible space,a space which she--as a person with a disability--wouldn't be able to enter. She said it wasn’t right, and given the values of WGS, it was hypocritical. I responded quickly: yes, she was correct, but those spaces are so limited at CofC! And I’m out of town right now! And there’s nothing I can do, but I’ll certainly keep this in mind for the future. She wrote back, dismissed my excuses as offensive justifications of unjust behavior. I thought, “Holy crap! How dare she!”

Shortly after I got to Charleston, I suspect sometime during my first year, we had an event on campus that I sent out broad community emails to advertise. CofC is a campus that has very, very few spaces that are accessible. I got an email from a community member I didn’t know who told me in pretty clear-cut terms that I’d scheduled an event in an unaccessible space,a space which she--as a person with a disability--wouldn't be able to enter. She said it wasn’t right, and given the values of WGS, it was hypocritical. I responded quickly: yes, she was correct, but those spaces are so limited at CofC! And I’m out of town right now! And there’s nothing I can do, but I’ll certainly keep this in mind for the future. She wrote back, dismissed my excuses as offensive justifications of unjust behavior. I thought, “Holy crap! How dare she!”

Then, when I’d had a chance to get off my high horse and calm down, I thought, “She’s right.” I’d never try to justify behavior that was openly restrictive based on gender, or race, or sexual identity. What made me think it was okay to apologize for—and proceed with—behavior that was openly discriminatory based on ability?

I wrote her an email apologizing and promising that we’d find a new location for the event. And we found one. And she came.

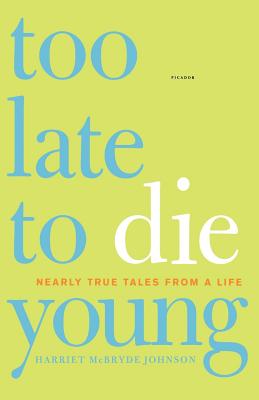

Her name was Harriet McBryde Johnson, and it turns out she was a brilliant disability activist. Her memoir had come out sometime shortly before our encounter, and I read it and remember enjoying it very much. Just this weekend I finished reading it a second time, and it has blown my mind.

I’ve read so many memoirs this summer by and about people with various disabilities. Hers is far better than many, many I’ve encountered. I’ll be teaching it in my graduate class (Disability, Power, and Privilege) this spring, and I suspect it'll show up again and again in my upcoming research and writing. It features statements like, “When bigotry is the dominant view, it sounds like self-evident truth.” And, “For over one hundred years, a powerful medical-industrial complex has trained us to think that people judged unable to care for themselves must, for their own good and the good of society, be consigned to government-funded lockup. Even forward-looking thinkers don’t recognize the incarceration of some two million Americans in nursing homes, psychiatric facilities, and other institutions as a human rights violation.” And, “We need to confront the life-killing stereotype that says we’re all about suffering. We need to bear witness to our pleasures.”

Johnson died just a little over two years ago, here in Charleston. I’ve already learned so much from her: she’s the first person ever to call me out on my discriminatory behavior (and thinking!) about disabilities. But now that my politics, my feminism, and my life are growing more intimately connected with disability studies and disability activism, I see that I could have learned much more from her in person. She started coming to WGS events. She and I had a friendly acquaintanceship. I’m really sorry that I didn’t have the good sense to pursue her as a mentor when I had the opportunity.

11 years ago

2 comments:

I don't remember how I found your blog, but I've been reading for several months now. I picked this book up, solely because you mentioned it. I thought, "Huh. You know, I need to know more about this." Since having my son, my meter for -isms (racism, classism, ableism, sexism, etc.) has sharpened dramatically, but I came to realize that my literature was lacking in all but the sexism category.

This book was incredible. I wish so much that I had been able to read it as part of a class. There was so much that I wanted to talk about.

I have a running list of "People I would love to invite to dinner," made up mostly of people I'm not likely to ever have the chance to actually have to dinner - Harriet McBryde Johnson is now on the list. (As are you. :-))

So glad you enjoyed the book! And I wish we could have had dinner with Harriet McBryde Johnson--would have been so cool.

Post a Comment